Table of Contents

- What is a Web Design Contract?

- What to Include in Your Web Design Contract

- 4. Protect Yourself Against Copyright Infringement

- 5. Make Sure the Agreement Designates a Legal Jurisdiction Near You

- 6. Format Your Agreement So It Doesn’t Scare Your Prospective Clients

- Have an Attorney Draft Your Contract — You’ll Thank Yourself Later

By Frank Olivo and Laura J. Neville, Esq.

The first day back to work after New Year’s, we got a certified letter from a client. His project was pretty much finished, and we were waiting for final approval to launch it, but we hadn’t heard from him in a few months.

We opened up the letter to discover that he was accusing us of being in breach of contract and demanding a full refund for the project. Our office attempted to get him on the phone, but he refused to speak with us.

Three weeks later, we ended up finishing the project, getting paid in full, and receiving an apology from him. He even paid extra for items that were additions to the scope of the project.

This would not have been possible had it not been for our web design agreement.

I own a web development and SEO agency outside of Philadelphia. My co-author is an attorney that handles all of the content for our law firm clients, and between the two of us, we’ve seen it all.

This post is going to walk you through a number of essential elements and clauses that your agreement must have to help you handle common scenarios that derail web design projects — no matter if you are a freelancer or a small business working with WordPress or any other platform. .

We’re going to talk about the most common pitfalls that we’ve encountered and how having certain clauses in your web development contract can both protect you and save you time and money.

Important – we are not providing you legal advice. The purpose of this post is to get you to consider the common scenarios that arise with web development projects.

You should discuss these scenarios (and more) with an experienced contract lawyer who can draft a binding agreement that will help you to prevent your business from losing time and money.

What is a Web Design Contract?

A web design contract is a social document that details the legally enforceable agreement between a designer and their client. It defines the business relationship between the two parties and details the project scope, pricing, deliverables, timelines, and other pre-agreed items relevant to the project.

In addition, the contract should outline what happens in case of problems or disagreements that may arise between the designer and their client.

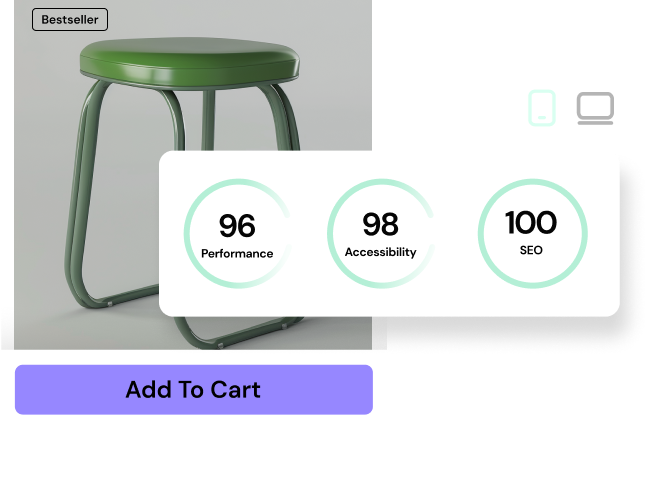

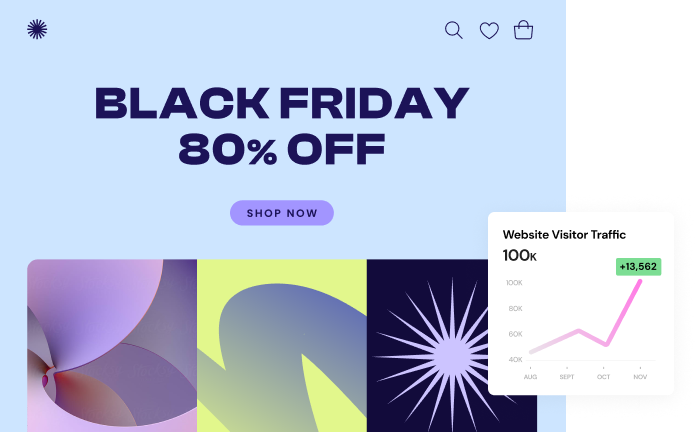

Grow Your Sales

- Incredibly Fast Store

- Sales Optimization

- Enterprise-Grade Security

- 24/7 Expert Service

- Incredibly Fast Store

- Sales Optimization

- Enterprise-Grade Security

- 24/7 Expert Service

- Prompt your Code & Add Custom Code, HTML, or CSS with ease

- Generate or edit with AI for Tailored Images

- Use Copilot for predictive stylized container layouts

- Prompt your Code & Add Custom Code, HTML, or CSS with ease

- Generate or edit with AI for Tailored Images

- Use Copilot for predictive stylized container layouts

- Craft or Translate Content at Lightning Speed

Top-Performing Website

- Super-Fast Websites

- Enterprise-Grade Security

- Any Site, Every Business

- 24/7 Expert Service

Top-Performing Website

- Super-Fast Websites

- Enterprise-Grade Security

- Any Site, Every Business

- 24/7 Expert Service

- Drag & Drop Website Builder, No Code Required

- Over 100 Widgets, for Every Purpose

- Professional Design Features for Pixel Perfect Design

- Drag & Drop Website Builder, No Code Required

- Over 100 Widgets, for Every Purpose

- Professional Design Features for Pixel Perfect Design

- Marketing & eCommerce Features to Increase Conversion

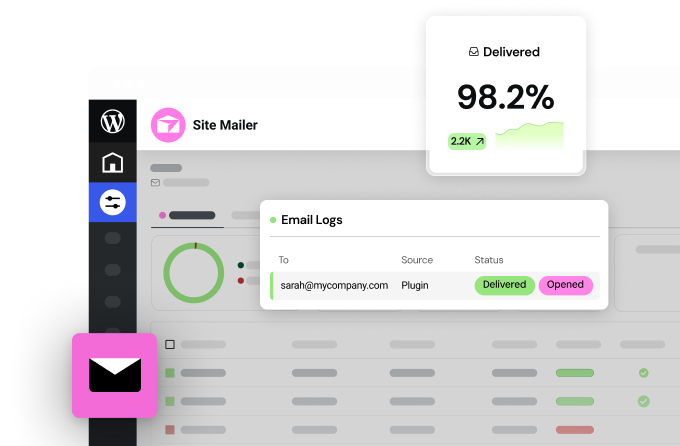

- Ensure Reliable Email Delivery for Your Website

- Simple Setup, No SMTP Configuration Needed

- Centralized Email Insights for Better Tracking

- Ensure Reliable Email Delivery for Your Website

- Simple Setup, No SMTP Configuration Needed

- Centralized Email Insights for Better Tracking

- Ensure Reliable Email Delivery for Your Website

- Simple Setup, No SMTP Configuration Needed

- Centralized Email Insights for Better Tracking

What to Include in Your Web Design Contract

- 1. Have a Clearly Defined Statement of Work

- 2. Streamline the Review and Approval Process

- 3. Protect Yourself in the Case of Project Termination

- 4. Protect Yourself Against Copyright Infringement

- 5. Make Sure the Agreement Designates a Legal Jurisdiction Near You

- 6. Format Your Agreement So It Doesn’t Scare Your Prospective Clients

- → Web Design Contract Template

1. Have a Clearly Defined Statement of Work

Define What Is in Scope and Stick to It

The scope of work is your starting point. You need to list absolutely everything that you’re going to do for the client.

If you start performing services or adding features that are not in the statement of work, you’re going to set expectations that will result in either scope creep or a dissatisfied client.

By laying out absolutely everything that you’re going to do very clearly, there won’t be any surprises when you get a request, and you politely tell them that you can do it, but it’s going to extend the scope and cost more.

If your statement of work omits some things that you wind up doing anyway, you’re opening the door for scope creep.

Be sure to include the deliverable you are going to provide. If there’s going to be browser testing or other services that are not usually mentioned be sure to mention it.

Also, include the payment terms, and the payment schedule (including any deposits you are going to ask to be paid upfront) for your website development services. Make sure that you understand all the costs that you may be required to incur over design services, hiring a web developer, etc.

Try to Anticipate Areas of Potential Scope Creep and Explicitly List Them as “Out of Scope”

While most developers are pretty good about including what is in scope, very few explicitly state what is out of scope.

This is a tremendous mistake.

Unfortunately, experience is the only way to learn what needs to be explicitly marked as out of scope, but here are a few items we mark as out of scope pretty regularly:

- Listing of over x-number of products for ecommerce stores

- Keyword research and writing of title tags and meta descriptions (unless the client pays for it)

- Proofreading of copy the client provides (especially when it’s a redesign of an existing website that reuses copy)

- Design changes once mockups have been approved and we have started building

- Organization of content such as photos and copy. If you are dealing with a website that is going to have hundreds of pages — which is extremely common when dealing with ecommerce sites — it is the client’s responsibility to make sure that it is all well organized.

This is far from exhaustive, but it should get the gears turning and save you a lot of headaches down the road.

Include a Provision That Outlines How You Will Handle Out-Of-Scope Requests

It’s crucial to have a clause that outlines how you were going to handle scope extensions.

Your client is not a developer. He doesn’t necessarily understand how involved it can be to go back and redo something that you’ve already started, which is often the case when there are changes to the scope of the project.

By starting a project with a clear understanding that there will be additional costs if any new features are requested, your client is highly unlikely to get upset if you tell him there’s going to be a small additional charge for his newest and greatest idea.

This clear understanding needs to be reinforced with a clause that explains how you intend to handle scope extensions.

2. Streamline the Review and Approval Process

We all deal with this.

We send over a mockup and don’t hear from the client for six months.

This is usually not the client’s fault. They likely have a ton of other responsibilities to tend to, and the website is often overlooked in favor of more important things — like actually running a business and making money.

This doesn’t mean that approvals need to take six months.

Set Review and Approval Windows in Your Agreement

Include a clause that gives a specific number of days for a client to review designs and get back to you.

Ours states that the design is considered “approved” after x number of days. You might think that you’ll get resistance on this, but it simply isn’t the case.

Your clients want their projects done in a timely fashion just as you do. By including this provision in your agreement, you’re likely to send the message that you’re intent on getting everything done efficiently.

Approval Windows Will Get Your Clients Moving

By establishing approval windows in your agreement, you will give the client a good reason to get back to you. Our agreement usually gives the client a 7 to 14 business day window to approve design mockups — once that window has expired, the design is considered approved.

We don’t use this clause to hammer our clients over the head. As a matter of fact, we’ve never had to enforce it! Since there’s a clear understanding from the outset that they need to get back to us in two weeks or possibly pay more for their project than anticipated, they get back to us in a timely fashion.

Handling Clients Who Take Forever to Deliver Content

Our current standard agreement does not address this, but it probably should.

It is not unheard of for web development contracts to include a fee for “re-starting” a project that has gone dormant. Again, the goal isn’t to squeeze money out of your client; the purpose is to get him to prioritize getting you what you need to do your job.

If your client knows that it’s going to cost extra if he takes four months to send you copy, he’s going to have more of a reason to get it to you in a timely fashion.

How Many Rounds of Revisions is a Client Entitled To?

First, if you are unable to deliver satisfactory designs in 5 to 7 rounds, you’re either doing something wrong, or you should have seen the red flags before you even started the project.

The real reason to establish a limit on revisions is not to get clients to approve mockups they are unhappy with, but to keep the client organized.

Without a limit on rounds of revisions, you are practically guaranteeing yourself a death by 1000 emails. Once a client knows he is “using up” a round of revisions, he’s more likely to go through the design thoroughly and send you a complete list of requests that can be handled in one sitting. You might also include a sentence providing that all revisions shall be set forth in one email, all at once, and not piecemeal over several emails.

3. Protect Yourself in the Case of Project Termination

Your client may want to end a project prematurely for any number of reasons. Here’s a list of a few reasons we’ve had projects terminated in the last year:

- The owner of the business died

- The website was for a pet project of an executive that was fired

- The business simply went out of business

- I kicked the client out of our office because he was being disrespectful to our employees

- The client was under the impression that we still owed him revisions when everything had been completed (this was the case of the client mentioned at the beginning of this article)

In each one of these cases, we were paid what we were owed. This is only because of the clauses in our project contracts that address the termination of the contract.

Be Compensated for Hours Worked

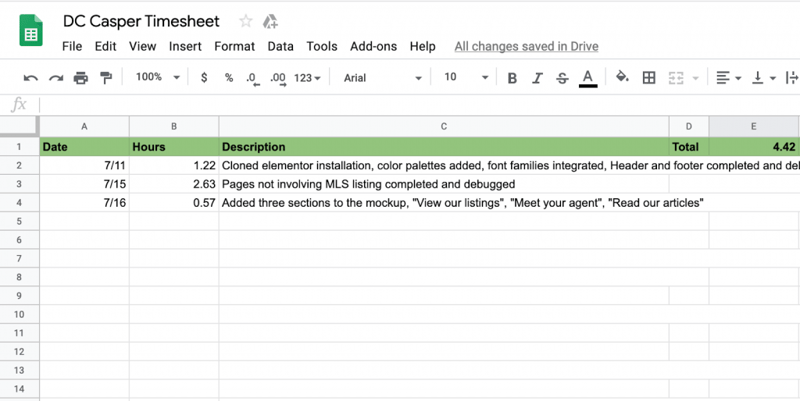

When clients wish to terminate our contract, they agree to compensate us for the hours we have spent on it. You should have a similar clause in your contract, and you should be tracking hours spent, even if only for the purpose of operations management and your accounting.

Such a clause can prevent you from losing money and wasting time if the client decides to cancel the project. This does happen often enough, yet these clauses are strangely absent from many web development agreements.

We use Google Sheets for time tracking. The good thing about this is that it can be used by your entire team, you can set it to be viewable by the client, and it is time-stamped, so it is a bit more trustworthy than you claiming you worked X amount of hours.

Establish How Breaches of Contract are Handled

If either party accuses the other of being in breach of contract, there should be a clause that allows for the accused party to address the breach within 30 days.

This was what saved the project I mentioned at the beginning of this article

I promptly responded to our clients’ letter with a certified letter pointing out this clause and presented two options: end the project and pay for our hours worked (as stipulated in the contract), or allow us to complete whatever revisions he still wanted and had not provided.

He chose the latter (and later realized how unreasonable he had acted).

4. Protect Yourself Against Copyright Infringement

A couple of years ago, we had a client insist that we use copyrighted images from major-league baseball on his tour website.

He did not have permission to use any of them, which would constitute copyright infringement.

We were very clear that using these pictures could potentially get him sued, but he insisted, and we used them.

Luckily, he was never sued, but even if he had been, we were protected by our agreement.

In most cases, you don’t have to worry about such blatant copyright infringement. The kind of infringement that you’re more likely to encounter is in the form of photos that your client pulled off of a Google image search and included in the assets to go on his new website. You may also encounter infringement in terms of text content.

If you are not indemnified against such copyright infringement, you could be found liable in some jurisdictions. You should have some sort of clause that protects you in case your client provides you with copyright-infringing assets.

Additionally, it’s a good idea to include an intellectual property rights clause that protects your personal work and anything that you won’t be giving to the client.

5. Make Sure the Agreement Designates a Legal Jurisdiction Near You

To a lawyer or anyone that’s ever taken a business law class, this is a no brainer. However, it is not uncommon for web designers to write up their own web design contracts and leave this out. If you do, it can result in a world of headaches and fees if your client sues you.

Let’s say, for instance, you’re located in New Jersey, and you’re building a website for a company in Utah. If you do not set forth the applicable law and forum in your agreement, you might end up having to go to Utah if your client decides to sue you over something — even if the suit is entirely without merit.

In the applicable law section of your agreement, state what country or state’s laws govern the agreement and where the forum is (your home state, presumably). Be aware that as of the date of this post, under U.S. law, you and your client can sue in federal court in the jurisdiction where either resides if the amount in controversy is more than $75,000. Specifying that litigation is governed by the laws of your home state and shall take place in your home state court can keep your case out of federal court.

You can also set forth how a conflict will be handled. For example, you might specify an alternative to litigation, such as having a third party arbitrator render a binding decision and that the cost of binding arbitration will be shared by the parties. Binding arbitration is much less expensive and time-consuming than litigation and is more likely to preserve your relationship with your client and keep the project viable.

6. Format Your Agreement So It Doesn’t Scare Your Prospective Clients

When we first had our web design agreement drawn up, it was nine pages long.

At the moment of sitting down at the table to sign it and get started, they would look at it as if I just handed them an agreement to sell their home.

We would almost always spend a ton of time going through it. In many cases, especially when sending it via email, they would send it back with notes and questions. Overall, the length and format of the contract created a lot of friction right at the closing of the deal.

At the recommendation of a fellow agency owner, we implemented a one-page rule.

Today, our agreement is no longer than one page, and we rarely get any pushback when it comes to closing a deal and getting started with a new project.

When you take a look at the difference between the two, you’ll understand why this is the case.

Ready to sign that client? Download our Web Design Contract Template.

Have an Attorney Draft Your Contract — You’ll Thank Yourself Later

We highly recommend that you find an attorney you can trust.

A good contract lawyer will be able to draft a web development agreement and any other legal documents that will protect you. Lawsuits are almost inevitable when running a business — a small investment now can potentially save you a fortune later on.

Laws can vary greatly from state to state and country to country, so it is essential for you to find a good attorney in your jurisdiction to draft your web development agreement.

We suggest you discuss these six topics and legal terms with this attorney. By preparing for these extremely common scenarios in web design projects, you’ll save yourself time, money, and headaches, while preserving client goodwill and satisfaction with your work.

In addition to the contract, you will also need to a web design project proposal to get things going. Check out Elementor’s great guide on how to create a project proposal.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this article, as well as in the free template of the sample contract is for educational purposes only. We suggest that you consult with a professional lawyer to draft a legal, binding contract for your legal needs. Elementor does not take any responsibility for any problems or issues that may arise, should you decide to rely solely on the information provided in the article or the sample contract/template.

Frank is the founder of Sagapixel, an SEO and web design firm with offices in New Jersey and Philadelphia. Frank is an alumnus of Rutgers University and holds an MBA from the Fox School of Business at Temple University.

Laura oversees content for law firm SEO clients at Sagapixel. Ms. Neville has practiced law in Pennsylvania and New Jersey since 2006. She graduated from Temple University, Trenton State College, and Rutgers School of Law – Camden.

Looking for fresh content?

By entering your email, you agree to receive Elementor emails, including marketing emails,

and agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.