Table of Contents

The first website was created by British physicist Tim Berners-Lee in 1990 while he was working at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, in Switzerland. It wasn’t designed for commerce, entertainment, or social connection. Its purpose was far more practical: to be an instruction manual for a revolutionary new system of information sharing he had just invented. This article will journey back to that pivotal moment, exploring the “what,” “why,” and “how” of this digital starting point and tracing its incredible legacy to the powerful web creation tools we use today.

Key Takeaways

- Who and Where: The first website was created by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Switzerland.

- When: The site first became operational on December 20, 1990, and was made available to the wider public in August 1991.

- The Address: The URL for the first website was http://info.cern.ch. A restored version of the site is still active today.

- The Technology: Berners-Lee invented the three core technologies that made the web possible: HTML (HyperText Markup Language) for structuring pages, URL (Uniform Resource Locator) for addressing them, and HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) for retrieving them.

- The Purpose: The website was a meta-document. Its content explained the World Wide Web project itself, providing information on how to create webpages and how to search for information.

- The Tools: The site was built on a NeXT computer, which served as both the first web server and the first web browser, which was also an editor called WorldWideWeb.

- The Legacy: CERN’s decision in 1993 to make the World Wide Web technology royalty-free was the catalyst for its explosive global growth, leading directly to the internet as we know it today.

The World Before the Web: A Glimpse into a Disconnected Era

To truly appreciate the seismic shift triggered by the first website, we have to understand the digital environment from which it emerged. In the late 1980s, the “internet” existed, but it was not the user-friendly, graphical space we know. It was a collection of networks, primarily used by academics, researchers, and the military. Accessing information was cumbersome and required specialized knowledge.

The Need for a Universal Information System

Imagine a massive, global organization like CERN. Thousands of scientists from universities and institutions all over the world collaborated on complex physics experiments. They generated vast amounts of data, wrote papers, and needed to share their findings. The problem was that this information was trapped.

It existed in a digital Tower of Babel. Data was stored on different types of computers, from IBM mainframes to Macintoshes, each using different networking protocols and proprietary file formats. To get a piece of information from a colleague’s machine, you often needed to have the same type of computer, the same software, and a direct network connection. There was no universal “space” where information could live and be accessed by anyone, from anywhere.

Several precursor technologies tried to solve parts of this problem:

- ARPANET: The forerunner to the modern internet, ARPANET was a US military project that proved the concept of a decentralized computer network. It was the backbone, but it wasn’t a user-friendly information system.

- Usenet: This was a worldwide discussion system, like a distributed network of forums or “newsgroups.” Users could post messages and read replies, but it was primarily for discussion, not for linking and organizing static documents.

- Gopher: Developed at the University of Minnesota, Gopher was a menu-based system for browsing files on the internet. It was a significant step forward, presenting information in a structured hierarchy of folders and files. You could navigate from one server to another, but it lacked the fluid, non-linear linking that would define the web.

Each of these systems was a piece of the puzzle, but none provided the complete solution. What was missing was a single, simple, and universal way to link documents together, regardless of where they were stored.

The Visionary: Who is Tim Berners-Lee?

Into this complex environment stepped Tim Berners-Lee. A British computer scientist with a background in software engineering, Berners-Lee was working at CERN as a contractor. He had previously developed a personal database called “Enquire,” which used bidirectional links to connect information—an idea that would become central to his later work.

He saw the frustration at CERN firsthand. He understood that the organization’s real product wasn’t just data from particle accelerators; it was the web of knowledge connecting people, experiments, and research. In March 1989, he wrote a proposal titled “Information Management: A Proposal.” It was a dry, technical document, but its vision was anything but.

His boss, Mike Sendall, famously scribbled “Vague, but exciting…” on the cover and gave him the green light to work on the project. The proposal outlined a decentralized information system based on a simple but profound concept: hypertext.

The idea of hypertext—text that contains links to other texts—was not new. Thinkers like Vannevar Bush had conceptualized it decades earlier. But Berners-Lee’s genius was in applying it to a global network of computers. He envisioned a world where any document could link to any other document, creating a universal, interconnected “web” of information. This simple proposal was the blueprint for the modern internet.

The Birth of the Web: Building the Foundation

With his proposal approved, Tim Berners-Lee set out to build the tools necessary to bring his vision to life. He wasn’t just creating a piece of software; he was inventing an entire ecosystem. Between September and December of 1990, he single-handedly developed the fundamental technologies that still power the web today.

The Three Pillars of the Web

Berners-Lee understood that his system needed three core components to function: a way to write documents, a way to address them, and a way to transmit them.

- HTML (HyperText Markup Language): This was the language for creating web pages. It wasn’t a complex programming language but a “markup” language. It used simple tags to define the structure of a document. The very first version of HTML was incredibly basic, with only about 18 tags. These included tags for a title (<TITLE>), headings (<H1>, <H2>, etc.), paragraphs, and, most importantly, the anchor tag (<A>) for creating hyperlinks. This provided the “skeleton” of every webpage.

- URL (Uniform Resource Locator): This was the solution to the address problem. A URL provided a single, consistent way to locate any resource on the web. Whether it was a document, an image, or a video, it would have a unique address that any browser in the world could understand. The first URL followed a simple structure: protocol://hostname/path. For example, http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html. This innovation ensured that the web could scale globally without chaos.

- HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol): This was the engine of the web. HTTP is the protocol, or set of rules, that a web browser (the client) and a web server use to communicate. When you click a link, your browser sends an HTTP “request” to the server asking for the document. The server then finds the document and sends it back in an HTTP “response.” This simple, stateless request-response cycle is the invisible transaction that happens billions of times a second across the globe.

The Tools of Creation: The First Browser and Server

To build and demonstrate these three pillars, Berners-Lee needed hardware and software. He found the perfect tool in a machine built by a company founded by Steve Jobs after he had left Apple.

- The NeXT Computer: This was a powerful and advanced workstation for its time. Crucially, it had a graphical user interface and powerful object-oriented development tools that made it relatively easy for Berners-Lee to quickly build the software he needed. This single black cube would become the cradle of the World Wide Web.

- The WorldWideWeb Browser: On the NeXT machine, Berners-Lee wrote the first-ever web browser. He named it, fittingly, WorldWideWeb (it was later renamed Nexus to avoid confusion with the web itself). This browser was a true “What You See Is What You Get” (WYSIWYG) application. But its most remarkable feature is one that has been largely lost in modern browsers: it was also an editor. A user could browse the web and, if they had permission, click an “Edit” button and start typing directly onto the page, creating new links and saving their changes back to the server. Berners-Lee’s original vision was a collaborative, two-way medium, where consuming and creating content were equally simple.

- The First Web Server: The same NeXT computer also ran the first web server software, httpd. A web server is simply a program that listens for incoming HTTP requests from browsers, locates the requested files (the HTML documents), and sends them back. Berners-Lee’s NeXT machine was the first computer in history to perform this task. He famously put a sticker on it that read: “This machine is a server. DO NOT POWER IT DOWN!!” This single computer was, for a time, the entire World Wide Web.

The First Website: A Deep Dive into info.cern.ch

With the core technologies and tools in place, the final step was to create the first webpage. On December 20, 1990, Tim Berners-Lee published the first website on his NeXT server. The address was http://info.cern.ch. Initially, it was only accessible to those within the CERN network. It wasn’t until August 1991 that he announced the project on public internet newsgroups, making it available to the world.

Deconstructing the Homepage

So, what was on this revolutionary first page? There were no flashy graphics, no videos, no complex layouts. It was a simple, text-based page with a white background and blue hyperlinks. Its content was entirely self-referential. It was a website about the World Wide Web itself.

The homepage served as an introduction and a guide to this new project. It explained what the World Wide Web was, how it could be used, and how people could get involved. It had links to other pages that provided more detail, such as:

- A summary of the project.

- Information about the people involved.

- Instructions on how to create your own web server.

- A list of other web servers as they came online.

- Technical specifications for the protocols (HTTP, HTML).

The design was purely functional. Its beauty was not in its aesthetics but in its utility and its underlying concept. Every page was a node of information, and the hyperlinks were the threads connecting them.

The Power of the Hyperlink

The truly revolutionary aspect of that first website was the hyperlink. Before the web, navigating digital information was like walking down a corridor, opening one door after another in a linear sequence (as with Gopher’s menus). The hyperlink shattered that model.

With a simple click, a user could jump from a concept on one page to a detailed explanation on another, hosted on a completely different computer thousands of miles away. It allowed for a non-linear, associative train of thought, mirroring how the human brain makes connections. This was the “web” made manifest—an interconnected mesh of knowledge that could grow organically and without any central control. It was this feature that would allow the web to scale from a single server at CERN to the billions of sites we have today.

The Aftermath and Explosion of the Web

The launch of the first website was not a thunderous event. It was a quiet beginning, a tool created for a niche community of physicists. But the seed had been planted, and two key events would cause it to grow at an exponential rate.

From CERN to the World: Making the Web Public

The single most important decision in the history of the web came on April 30, 1993. CERN’s directors announced that the technology of the World Wide Web—the code for the server, the client, and the library of protocols—would be made royalty-free and available to everyone.

This was a profoundly altruistic and far-sighted decision. By putting the technology in the public domain, CERN ensured that no single company could own or control the web. It created a level playing field, inviting anyone and everyone to build upon Berners-Lee’s foundation. This act of digital generosity was the catalyst that ignited the web’s explosive growth.

The Rise of the Browsers and the Early Web

While Berners-Lee’s WorldWideWeb browser was powerful, it only ran on the expensive NeXT computers. For the web to take off, it needed a browser that could run on the everyday computers people were using.

In 1993, a team at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois released the Mosaic browser. Mosaic was a game-changer for two reasons. First, it was easy to install on most common operating systems, including Windows and Mac. Second, and most famously, it was the first browser to display images inline with text, rather than in a separate window.

Suddenly, the web was no longer just a tool for text. It became a visual, multimedia experience. This made the web accessible and appealing to a much broader audience, far beyond the scientific community.

The success of Mosaic led directly to the formation of Netscape and its wildly popular Netscape Navigator browser. This, in turn, sparked the first “browser war” as Microsoft scrambled to catch up by integrating Internet Explorer into its Windows operating system. This fierce competition, while messy, rapidly accelerated the development of new web technologies.

The mid-to-late 90s saw the first wave of user-created websites. They were characterized by a quirky, experimental aesthetic: flashing animated GIFs, visitor counters, “under construction” signs, guestbooks for leaving messages, and webrings that linked sites with similar topics.

The Dot-Com Boom and the Commercialization of the Web

It wasn’t long before businesses realized the immense potential of this new global platform. The web transitioned from an academic and hobbyist project into a commercial juggernaut. Companies like Amazon (started in 1994 as a bookstore) and eBay (started in 1995 as an auction site) pioneered the concept of eCommerce. This led to the “dot-com” bubble of the late 1990s, a period of massive investment and speculation in internet-based companies. While the bubble eventually burst, it cemented the web’s role as a central pillar of the global economy.

The Evolution of Web Creation: From Hand-Coding to Visual Builders

The journey from that first, simple page at CERN to the dynamic, interactive websites of today is also the story of how websites are made. The tools and processes have evolved dramatically, consistently moving towards greater accessibility and power.

The Age of the Webmaster: Hand-Coding with HTML and CSS

In the early days, creating a website was the exclusive domain of the “webmaster”—a technically proficient individual who could write code. The process involved typing out HTML tags in a basic text editor like Notepad and then uploading the file to a server using a program like FTP.

Styling was minimal until the introduction of Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), which allowed for the separation of a page’s structure (HTML) from its presentation (colors, fonts, layout). This was a major step forward, but it still required creators to learn two different coding languages.

Tools like Adobe Dreamweaver and Microsoft FrontPage emerged to make this process easier. They offered a more visual interface, allowing users to design pages without writing every line of code by hand. However, they were still complex, expensive pieces of software that produced clunky code and required a significant learning curve.

The CMS Revolution: The Rise of WordPress

The next great leap forward was the advent of the Content Management System (CMS). A CMS is a software platform that separates the content of a website from its design and functionality. This meant that a writer could add a new blog post or a product manager could update a product description without needing to touch any code or consult a developer.

While several CMSs exist, one platform rose to dominate the web: WordPress. Originally launched in 2003 as a simple blogging tool, WordPress evolved into a full-fledged CMS capable of running any type of website, from personal portfolios to massive news sites and online stores. Its open-source nature and vast ecosystem of themes and plugins made it incredibly flexible and popular, and today it powers over 40% of the entire web.

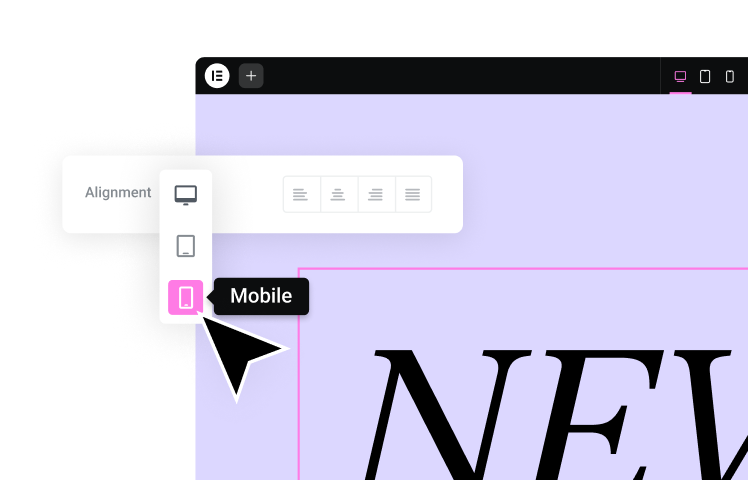

The Visual Builder Era: Empowering Creators without Code

Even with a CMS like WordPress, extensive customization still often required coding expertise. The latest evolution in web creation has been the rise of visual, drag-and-drop website builders, which bring the process full circle, back to the WYSIWYG spirit of Tim Berners-Lee’s original browser/editor.

These tools represent a fundamental shift, empowering users to design and build sophisticated websites in real-time without writing a single line of code. At the forefront of this movement is Elementor, a complete website builder platform that has transformed how creators approach WordPress.

Platforms like Elementor provide an intuitive visual interface where you can drag elements like headings, images, and forms directly onto a canvas and style them with granular control. This has democratized the world of professional web design, making it accessible to designers who want to realize their vision without code, entrepreneurs who need to build their own online presence, and agencies who need to build client sites efficiently.

As web creation expert Itamar Haim notes, “The journey from Tim Berners-Lee’s first, purely functional HTML page to today’s visually rich websites built with platforms like Elementor is a story of progressive democratization. We’ve moved from requiring deep technical knowledge to empowering creative vision directly, allowing anyone to build a professional online presence.”

The Modern Web Creation Stack

Building a website today involves more than just a builder. It’s an integrated stack of tools working together.

- Hosting: A website needs a place to live. In the past, this meant navigating complex hosting panels and dealing with conflicts between plugins and server settings. Modern solutions like Elementor Hosting provide a seamless, all-in-one environment specifically optimized for the builder. This integrated approach ensures peak performance and reliability, especially for demanding sites like those requiring eCommerce hosting.

- Themes & Templates: Instead of being locked into a rigid theme, modern workflows use flexible theme frameworks and extensive template libraries. Platforms like Elementor offer foundational themes that act as a clean slate, giving the creator total design freedom.

- Functionality: The power of modern web creation lies in its extensibility. With Elementor Pro, creators unlock advanced features like popup builders, form builders, and a powerful WooCommerce Builder for creating custom online stores.

The Future is AI and Automation

The evolution doesn’t stop. The next frontier in web creation is Artificial Intelligence. AI is no longer a futuristic concept; it’s a practical tool that is accelerating workflows in incredible ways.

AI tools are being integrated directly into the creation process. For example, Elementor’s AI tools can generate text, create unique images from prompts, and even write custom code snippets on command. This frees creators from tedious tasks and helps them overcome creative blocks. The process can now start even before the first pixel is placed, with tools like the AI Site Planner that can generate an entire sitemap and wireframe from a simple description.

The pinnacle of this trend is the emergence of agentic AI, which can perform multi-step tasks. These tools are transforming the builder into a true AI Website Builder, where a user can give a high-level command and watch the AI execute the entire workflow.

Modern Considerations: What Berners-Lee’s Site Didn’t Need

The digital landscape of today is infinitely more complex than it was in 1990. Building a successful website now requires attention to factors that were non-existent when info.cern.ch went live.

Performance and Optimization

The first website consisted of a few kilobytes of plain text. It would load instantly on even the slowest connection. Modern websites are orders of magnitude larger, filled with high-resolution images, videos, and complex scripts. Site speed is now a critical factor for user experience and search engine rankings. A slow-loading site will be abandoned by users and penalized by Google. This has made tools that improve performance, like the Image Optimizer by Elementor which automatically compresses and converts images to next-gen formats, essential for any serious web project.

Web Accessibility (a11y)

Because it was purely text-based and used simple, semantic HTML, the first website was inherently accessible to users with disabilities. As websites became more visual and interactive, accessibility often became an afterthought. Today, there is a crucial and growing awareness of the need to build an inclusive web that is usable by everyone, regardless of their abilities. Web accessibility is not just an ethical imperative; it’s also a legal requirement in many parts of the world. Modern solutions are now being integrated directly into building platforms to help creators identify and fix accessibility issues.

Communication and Growth

Berners-Lee’s site was a one-way broadcast of information. A modern website is a two-way communication channel. It needs to reliably handle user interactions, such as contact form submissions, account registrations, and eCommerce purchase receipts. The notorious unreliability of default WordPress email has made solutions like Site Mailer by Elementor, which ensures transactional emails reach the inbox, a critical utility. Furthermore, websites are now hubs for business growth, requiring integrated marketing tools like Send by Elementor to manage email campaigns and automated workflows.

Domain Names and Branding

The URL info.cern.ch was purely functional and descriptive. Today, a domain name is a core part of a brand’s identity. Choosing the right name is a critical marketing decision, and for many, securing a free domain name with their hosting package is the first step in establishing their online presence.

Conclusion

From a single NeXT computer in a Swiss laboratory to a global network of billions of interconnected pages, the evolution of the website is a story of relentless innovation. The first webpage, in all its stark simplicity, contained the DNA of the entire digital world that would follow. Its core principles—openness, decentralization, and the connective power of the hyperlink—remain the bedrock of the web.

Tim Berners-Lee’s vision was not just to create a new technology but to empower people with it. He imagined a collaborative space for sharing knowledge and ideas. That vision is more alive today than ever before. The journey from hand-coding HTML in a text editor to visually crafting stunning websites with a drag-and-drop builder is the realization of that goal.

Modern platforms carry on this mission of empowerment, abstracting away technical complexity so that anyone with an idea can share it with the world. The tools have changed, but the fundamental spirit of that first website—to connect, to inform, and to create—endures. If you feel inspired to join this incredible legacy, you can start your own web creation journey with a free download and become part of the ever-expanding web.

Expansion: 10 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can I still visit the first website? Yes. CERN is dedicated to preserving this piece of digital history. You can visit a 1992 restoration of the original website at its original address: http://info.cern.ch.

2. Who created the second website? This is difficult to answer definitively as the early web grew organically. However, one of the very first web servers outside of CERN was set up at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) in California in December 1991. It hosted a database of scientific papers, making it one of the earliest websites in North America.

3. What was the first image ever uploaded to the web? The first photo was uploaded to the web by Tim Berners-Lee in 1992. It was a picture of Les Horribles Cernettes, an all-female parody pop band founded by employees at CERN. The image was edited in an early version of Adobe Photoshop and saved as a .gif file.

4. How big was the first website in terms of file size? The original homepage was extremely small by today’s standards. A plain HTML file with the amount of text it contained would only have been a few kilobytes (KB). For comparison, a single high-resolution photo on a modern website can be several megabytes (MB), thousands of times larger.

5. Did Tim Berners-Lee get rich from inventing the web? No. Tim Berners-Lee and CERN made the decision to release the World Wide Web technology for free, without patents or royalties. He has stated that this was essential for the web to achieve universal adoption. While he has received numerous awards, honors (including a knighthood), and a comfortable academic salary, he did not become a billionaire from his invention. He is currently the director of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), which develops web standards.

6. What is the difference between the Internet and the World Wide Web? This is a common point of confusion. The Internet is the massive, global network of computers—the physical infrastructure of servers, cables, and routers. The World Wide Web is a service that runs on top of the internet. It’s the system of interconnected documents and resources linked by hyperlinks and accessed via URLs. Think of the Internet as the roads and the Web as the system of addresses and signs that let you navigate those roads to find houses (websites). Other services like email, FTP, and video conferencing also run on the Internet.

7. What programming language was the first website written in? The website itself wasn’t written in a programming language but in HTML (HyperText Markup Language). The software that ran the server (httpd) and the browser (WorldWideWeb) was written in the Objective-C programming language on the NeXT computer’s operating system, NeXTSTEP.

8. How long did it take to build the first website? The foundational work took a few months. Tim Berners-Lee wrote his proposal in March 1989. He started developing the core technologies (HTML, HTTP, URL) and the first browser/editor in September 1990 and had the first website and server running by December 20, 1990. So, the initial development took about three to four months of focused work.

9. What was the purpose of the “.ch” in the first URL? The .ch is the country-code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Switzerland. The name is derived from Confoederatio Helvetica, the Latin name for the Swiss Confederation. Since CERN is located in Switzerland, its domain name logically used the Swiss country code.

10. How has the philosophy of web design changed since the first website? The philosophy has shifted dramatically. The first website was purely utilitarian. Its design was dictated entirely by its function: to present structured information and links clearly. Early web design in the 90s focused on novelty and experimentation, with an emphasis on graphics and animations. Modern web design is user-centric. It’s a multidisciplinary field that combines graphic design, user experience (UX) design, interface (UI) design, accessibility, and performance optimization. The goal is no longer just to present information, but to create an intuitive, engaging, and effective experience for the user.

Looking for fresh content?

By entering your email, you agree to receive Elementor emails, including marketing emails,

and agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.